It’s hard to imagine but way back one hundred years ago the cultural life of this country was very different. People were not watching The Apprentice on TV or even listening to The Archers on the radio. Books and newspapers were, of course, common but for most ‘ordinary’ people their entertainment was performances and music. The most powerful of these was the music hall.

In 1914 music hall was harnessed in the service of the war with patriotic songs calling on men to enlist and claiming that we’d be in “Berlin by Christmas”. In many ways this was propaganda from below. This was ordinary people swept up in the excitement of the war enthusiastically writing and performing pro-war numbers rather than a centralised, government ordered propaganda campaign.

You can see this in the tone of some of the songs that were far from respectable (for the time). For instance, this number saying that all the ladies love a man in uniform; “The Army and the Navy need attention, / The outlook isn’t healthy you’ll admit, / But I’ve got a perfect dream of a new recruiting scheme, / Which I think is absolutely it. / If only other girls would do as I do/ I believe that we could manage it alone,/ For I turn all suitors from me but the sailor and the Tommy,/ I’ve an army and a navy of my own!”

It’s worth remembering as well that the purpose of music hall was not to sit and passively listen to the acts but a communal sing-a-long. So in 1914 enthusiasm for the war was a collective act, not a solitary one – but as the war developed we can see a collective recognition of the horrors of war and even a grudging respect for those who opposed it.

John Mullen at Paris University wrote a fascinating article on the uses and abuses of music hall in the service of, and against, the war effort from 1914 – 18 which is well worth reading in its entirety. Mullen says “Looking first at those songs which aim at encouraging men to join up, or at justifying the war effort in traditional jingoistic manner, we find such titles as the following : “Three Cheers for the Red White and Blue”, “Be a Soldier, Lad of Mine”, “The Army of Today’s All Right”, “Won’t you join the army?”, “We don’t Want to Lose You (but We Think You Ought to Go)”, “For the Honour of Dear Old England”, “Boys in Khaki, Boys in Blue”, “Men of England, You Have Got to Go”, “You ought to join”, “Our Country’s Call”, “Let ‘em All Come, We’re ready”, and “March on to Berlin!”.’

As the war goes on the tone changes from quick victory to ‘pack up your troubles’ and then dreaming of returning home. No one believes they will reach Berlin anymore.

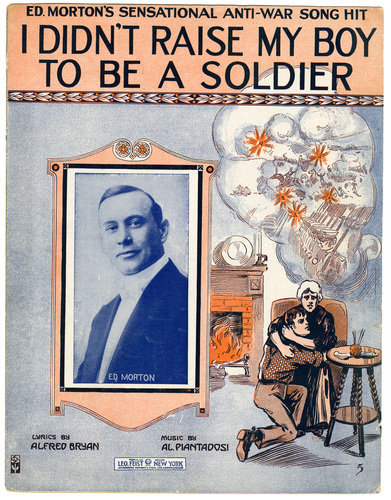

However, while patriotic pro-war sentiment was high we know that a large minority were not so sure or down right opposed. This has some reflection in the music hall, despite the fact that it was difficult to legally voice outright opposition. One popular song, first written for the US music hall became an international anti-war anthem and it’s not difficult to see why when we look at the lyrics of “I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier”; “I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier/ I brought him up to be my pride and joy/ Who dares to put a musket on his shoulder/ To shoot some other mother’s darling boy? / Let nations arbitrate their future problems/ It’s time to lay the sword and gun away/ There’d be no war today/ If mothers all would say/ “I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier”.”

Other songs were more subtle but no less subversive. In “The Military Representative” the policy of conscription taking anyone and everyone, no matter how ill suited, to fight was mocked with the military authority figure ridiculed as heartless and cruel before those pleading they could not or would not go to fight;

They called upon the next case/ Then a woman rose and said/ I’m very sorry gentleman/ But my poor husband is dead/ The chairman said “Well he’s exempted, he needn’t come again.”/ “Oh, thank you.” said the widow as she ran to catch a train/ But the military representative got up and shouted “Hi!!/ How dare your husband die! / He was A1 in July/ What say ma’am? He’s in heaven now? / Well you just let him know/ I’m sending a Sergeant to fetch him back/ For of course he’s got to go!”

They called on Rip van Winkle next and smiling all serene/ He mumbled “Gents, I’m 91, you’ve got me down 19!”/ (…) but the military representative got up and shouted “Say!”/ Don’t let him run away, though he’s 91 today!/ There are men down at the War office as old as he I know!/ And I’m sure they’re a damn sight sillier/ So of course he’s got to go!”

Soldier’s songs had the freedom of being less formal and so, ironically, were more likely to express high mutinous opinions in thoroughly robust language (skip the rest of this paragraph if you’d prefer to avoid swear words). John Mullen says “One well-known ditty wished that a particularly unpopular general, Cameron Shute would get shot : “For shit may be shot at odd corners/ And paper supplied there to suit/ But a shit would be shot without mourners/ If someone shot that shit Shute.””

The song A Conscientious Objector (which you can listen to here) is, on the face of it, a wry attack on those who refused to fight out of principle as effeminate cowards but scratch the surface and it’s far more complex. You can’t have an audience enthusiastically sing lines like the following and view this as a cut and dried anti-war song; “send out the bakers and blooming profit makers but for Gawd’s sake don’t send me.”

Likewise in “A bit of a Blighty one” (mp3) the artist takes on the voice of a soldier glad to have been wounded just enough to send him home (to Blighty) but not so much that he couldn’t enjoy being tucked in by the nurses; “so when they mop my brow with sponges and feed me with blanchemanges I’m glad I got a bit of a Blighty one.” Gone are the days of marching ever onwards to Berlin in favour of creature comforts and coming home.

So even in the music hall, where a show would have been shut down and the performers locked up if they’d been seen to agitate against the war, there was still space for a subversive message. Whether that be simply that the war wouldn’t be won so easily, the Generals were out of touch, cruel, fools or that the enemy were people just like us working class communities were clearly open to the idea that the war was not one of simply good against evil and that refusing to fight might, in fact, be a sensible, even honourable thing to do.